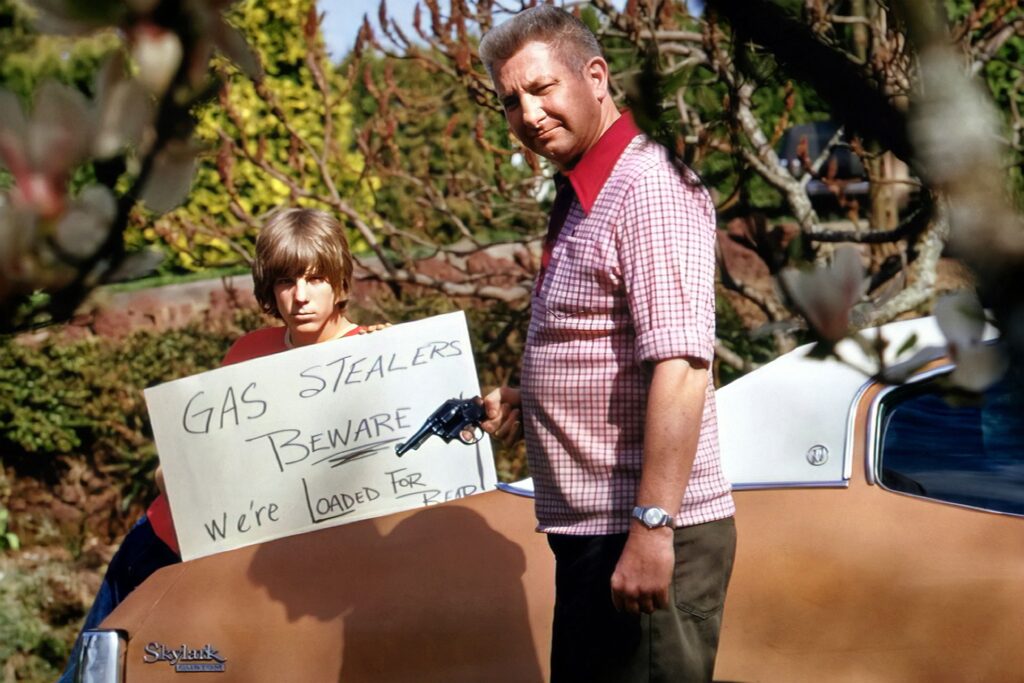

Cover Photo by Richard Bell

Anyone feeling a spot of nostalgia for the 1970s? Before you decide to pull out your flares, platform shoes and punk records, let’s take a look at what else characterised that fabled decade. For, it’s not only ABBA which has made a comeback in recent months. So has that dreaded economic phenomenon: stagflation.

But how similar is it to the original? After all, history doesn’t repeat as much as rhyme and falling on historical precedent may just be a little too convenient for an economic profession that can itself be accused of stagnating. There’s a crucial point to be made here. Namely, that if the problem is not accurately diagnosed, there’s a strong chance that the prescribed ‘solution’ will be found wanting.

Without going into full-on economics lecture mode, London Business Magazine brings you its take on our current juncture and why it differs from the 1970s global recession, in ways that numerous glib comparisons overlook.

Mists of time: What exactly happened in the 1970s?

Let’s dive into our time machine for a sec. The year is 1973. Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon is released, the US Supreme Court ruled on Roe vs Wade and tension in the Middle East leads to the Yom Kippur War. In response to the conflict, oil-producing countries in the region begin an embargo that sparks a shock in the global energy market.

Photograph courtesy of Documerica

The backdrop to this was double-pronged. On the one hand, the war in Vietnam had accelerated military spending and put pressure on a US Dollar that was already devaluing. On the other hand, newly emerging economies were beginning to challenge the industrial dominance of the Global North, whose productivity was struggling and lent itself to overheating.

Hence, predominantly cost-push inflation found itself confronted by a resurgent and combative labour movement. Wage increases were demanded to match the higher cost-of-living and industrial militancy became more commonplace. The concept of built-in inflation emerged, something often referred to as a ‘wage-price spiral’. Rising costs led to rising wages, with the increased labour cost being pushed to the consumer, who faced rising costs and so on.

Back to the future: What’s so different about now?

War, the fate of Roe vs Wade and an energy supply shock. So far, so similar. Although, all it takes is a step back and a look at the context to see where the similarities end.

Whilst the 1970s recession came off the back of three decades of strong and relatively stable economic advancement in Western economies, more recent economic growth has been anything but strong or stable – indeed, that’s if it’s been growing at all. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, wages have flatlined and in the UK, this sort of inertia hasn’t been seen since the Napoleonic Wars.

The labour movement in the Global North is a shadow of its former self and hence there has been minimal pushback against declining living standards in the past decade. So, reheated arguments over a new wage-price spiral are far off the mark. Not that it stopped even the likes of Andrew Bailey – Bank of England Governor – from suggesting that workers “think twice” before requesting a pay rise.

Another new development is the gradual decoupling of stock markets from the real economy, that has taken place this last decade. In short, while that part of the economy which concerns production, wages and the input/output of workers has stagnated, stock exchanges from the Nikkei to the Dow Jones hit record highs. Rather than interacting with each other, they have diverged fundamentally. This dissonance can be traced back to monetary and fiscal policy after the 2008 financial crisis, which caused asset prices to inflate while public spending and investment faltered.

Photo by Mika Baumeister

So, all in all, it’s hard to say that things were great before the global pandemic and subsequent war in Ukraine – two major events that finance ministries the world over point to, when addressing their critics. For sure, the shock to energy and food supply chains cannot be discounted but for those serious about finding a solution, the long view can’t be lost sight of.

Rising interest in raising interest

Solutions, anyone? There has been increasing talk of tightening monetary policy and raising interest rates to tackle inflation. However, if this is a solution, then what is the problem? Pushing up interest means that the cost of borrowing money increases, which might check demand-pull inflation but for businesses facing higher costs already, surely the recessionary effects of a rate rise will only make things worse. Case of the cure being worse than the disease?

To better target the solution, we need to ask who is most affected by inflation and why? The ‘who’ are predominantly those on lower and fixed incomes seeing their purchasing power being eroded. Small businesses that are not sitting on reserves of profit and assets are also struggling to stay afloat. The ‘why’ is overwhelmingly from – yes – higher fuel and food prices that are having knock-on effects across the wider real economy.

Time to get things under control?

Before we leave the 70s behind, there might be something there that could be of use to us today. Price controls. Or more specifically, price ceilings and particularly with regards to the energy market. The UK already has one – the energy price cap. Reducing it – instead of allowing it to shoot upwards – would drastically reduce costs for households and businesses, as well as halt the domino effect of rising prices elsewhere.

Some of the risks that come with price ceilings are unlikely to occur in this case, due to the natural monopoly nature of energy. We wouldn’t see energy companies suddenly hoarding gas and unregulated trading opening up. Food might be trickier, but this could be very specific to essential goods and for those lower-incomes who are already seeing price rises way above the official inflation rate.

To conclude, if the bankruptcy of modern-day economic thought is left unchecked, it could precipitate a bankruptcy of economic growth entirely. Blue-sky thinking is needed – after all, it’s just a notion.